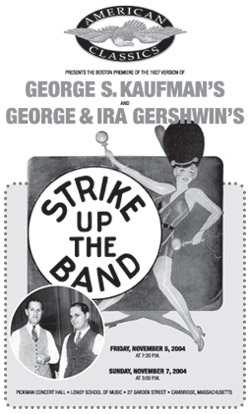

American Classics

Strike Up the Band was a critically acclaimed concert musical production presented by American Classics in 2004.

Please click here to listen to selections from the show.

"Satire is what closes on Saturday night." - George S. Kaufman

And so it was for his 1927 collaboration with George & Ira Gershwin, Strike Up the Band. The Saturday night in question was in Philadelphia, as the show never made it to New York. The irony of the closing is that this is a superb show. What went wrong? There are many answers, but the simplest is that the show was ahead of its time.

By 1927 both George S. Kaufman and the team of George & Ira Gershwin were leading figures on Broadway. Kaufman had served since 1917 as drama editor at The New York Times, and had written a number of Broadway hits with straight plays, including Dulcy (1921), Merton of the Movies (1922), and Beggar on Horseback (1924). The Gershwins had made their mark both as a team and with other collaborators. Together, they had written Lady, Be Good! (a 1924 vehicle for Fred & Adele Astaire), Tip-Toes (1925), and Oh, Kay! (1926, starring Gertrude Lawrence); George also had a string of hits from 1920 through 1924 with his scores for the annual revue George White's Scandals. A collaboration between Kaufman and the Gershwins seemed a perfect idea.

Kaufman may have disparaged satire, but he often used it in his shows, with a favorite target being big business. As Kaufman biographer Malcolm Goldstein says in George S. Kaufman, "the book [for Strike Up the Band] combined his now familiar dramatic theme, the self-serving instinct of the businessman - a theme just short of becoming an obsession with him - and a new concern, the folly of war." For George & Ira Gershwin, Kaufman's book gave them their first opportunity to write in the style of W.S. Gilbert & Arthur Sullivan, whose work they had admired since childhood. Using Gilbert & Sullivan as their model, the Gershwins wrote their first fully integrated score.

Satire, particularly political satire, inevitably has more plot than the standard boy-meets-girl story. Kaufman, besides pushing his themes, was averse to romance in his plays, so the romantic entanglements of Strike Up the Band play a small role in the story. It was the job of George & Ira Gershwin to provide much of the romance through their songs, even interpolating the hit "The Man I Love" to ensure a romantic ballad. "The Man I Love" had been dropped from Lady Be Good! in 1924, but by 1927 was popular in England, and the Gershwins felt that Strike Up the Band might offer an opportunity to place the song for American audiences. Ira wrote new lyrics for a second chorus sung by Jim, "The Girl I Love;" the added lyric is still rarely sung.

Kaufman was not as influenced by Gilbert & Sullivan as the Gershwins, though his script certainly has the flavor of Gilbert's skewering of institutions and unveiling the foolishness in human behavior. Philip Furia in his book Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist points out a major flaw in Kaufman's approach: " ... as Gilbert & Sullivan had shown, you must love what you satirize," noting that "in Strike Up the Band ... Kaufman satirized a subject he despised."

Using a "G&S" format meant a new innovation for the Gershwins, and a new twist for the Broadway musical: complete scenes carried by music, particularly in the Act I finaletto (the Act I finale being a staple of all the G&S operettas). Gilbert & Sullivan had a set formula for the construction of their operettas; the Gershwins adapted that formula to suit their needs.

Gilbert & Sullivan always open with a chorus of characters who are all the same (pirates, sailors, love-sick maidens). Strike Up the Band does the same, but the chorus introduces itself in madrigal style. While the madrigal was an important part of G&S operettas, it always appeared later in the show. G&S then have the principals enter, and introduce themselves in their own song. The Gershwins telescope this, using only one song (the opening chorus, "Fletcher's American Cheese Choral Society," following the madrigal introduction) in which the chorus and then a series of characters (Fletcher, Timothy, and Sloane) introduce themselves in a style reminiscent of the Pinafore Captain's entrance. Col. Holmes gets an entire introductory musical number to himself, based on that of Sir Joseph in HMS Pinafore. The rest of the show's characters are introduced through dialogue, not song.

Both Fletcher's "Typical Self-Made American" and Holmes's entrance ("Unofficial Spokesman") owe debts to HMS Pinafore. "Typical Self-Made American" takes elements of "When I Was a Lad" and "For He Is an Englishman;" "Unofficial Spokesman" also has roots in "When I Was a Lad," including a wonderful moment of Gilbertian topsy-turvy, in which Ira Gershwin has "the unofficial spokesman of the U.S.A.," Colonel Holmes, proudly aver that "he never says a word." In both cases, the clear message of Gershwin is the same as Gilbert: men who are blatantly unqualified have somehow risen to the top of their profession.

Using an operetta style meant that many scenes were played out musically, but the show still had songs which stood alone. "17 and 21," "Meadow Serenade" (both, unfortunately, dropped for the 1930 version), "Yankee Doodle Rhythm," "Military Dancing Drill" and, of course, the title song all were hummable and easily extractable from the score.

Allusions to current events and characters were a staple of Gilbert's writing. Ira Gershwin did not indulge in topical allusions to the extent of Gilbert or his own American counterpart Cole Porter, and those he did use were usually more slyly done than Porter's. Of Russian immigrant background, Ira was fond of playing with Russian names in his lyrics and in the "Patriotic Rally" slips Minsky and Rumshinsky into the mix, along with some non-Russians now barely remembered: silent film star Ben Turpin, actress Charlotte Cushman, actor Francis Bushman, banker Russell Cornell Leffingwell, and producer Morris Gest. In a list of mostly common male names in "The War That Ended War" he adds Isidor, which he long believed to be his given name (it was Israel).

Colonel Holmes, in "Unofficial Spokesman," is referred to as an F.F.V. (First Families of Virginia, meaning elite society), a K.C.B. (Knight Commander of the Bath, a British order which it is hard to imagine him obtaining), Z.B.T. (Zeta Beta Tau, a college fraternity which was mostly Jewish), and F.P.A. (the initials of popular humorous columnist Franklin Pierce Adams, in whose column, "The Conning Tower," many aspiring writers received their first publication). Many of these references were explained by Steven D. Bowen in the notes for the 1990 Nonesuch recording of the original Strike Up the Band, which is now - sad to tell - out of print.

The original production of Strike Up the Band featured Edna May Oliver, Jimmy Savo (who later played a twin opposite Teddy Hart in The Boys From Syracuse), and singer Morton Downey. Then, as now, these performers are not remembered for their star power, and it was that lack which was a factor in the show's early demise.

The critics were not necessarily hostile to the show; indeed, they seemed to be ahead of audiences in understanding what Kaufman and the Gershwins were attempting. Variety's reporter, Austin, assessed the show's chances perfectly: "That it will be a commercial smash is doubtful, but it will unquestionably have a succs d'estime." The succs d'estime took over sixty years to happen, but the original version of Strike Up the Band now holds a place of importance in both the output of the its creators and in the history of the American musical.

As the show was a flop, little documentation exists of it, with most writers repeating the same small group of anecdotes; since they involve quips by George S. Kaufman, they are anecdotes worth repeating. The most famous neatly illustrates both the humor of the creators and the tensions of bringing a show to fulfillment. As Ira Gershwin and George S. Kaufman were standing outside the theatre in Philadelphia, a pair of Edwardian-looking gentlemen went to the box office. Kaufman commented on them and Ira said, "That's Gilbert & Sullivan coming to fix the show." Kaufman shot back, "Why don't you put such funny lines in your lyrics?" The exchange is said to have occurred on a Saturday night.

– Benjamin Sears