American Classics

Fifty Million Frenchmen was a critically acclaimed concert musical production presented by American Classics in 2005.

Please click here to listen to selections from the show.

"Music theatre buffs got their chance last weekend to take in a rare concert performance of Cole Porter's early Broadway show '50 Million Frenchmen' performed by American Classics. Many of their regulars were in fine voice and ready to take on the broad, and sometimes racy lyrics and vintage jokes of this period piece." - Will Stackman, PNP Network,, 11/13/05

"American Classics has served us all very well once again with this splendid revival." - Norm Gross, Theatre Mirror,, 11/05

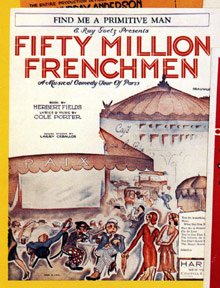

Cole Porter's (1891-1964) first successful Broadway shows were Paris (1928) and Fifty Million Frenchmen (1929). That Paris would be the subject of these (and later Porter shows) is no surprise, as he had lived in Paris since 1917, becoming part of the expatriate generation that included Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway; Porter would not return to America full time until 1937.

Porter had been a songwriter for many years, having written songs and shows during his years at Yale. Unlike his contemporary Broadway songwriters, Porter was born into a life of wealth and privilege, and did not need to rely on his songwriting to survive. On the strength of his successes at Yale, Porter wrote a Broadway show in 1916, See America First, which ran only fifteen performances (and received such reviews as "see America last"). With this early defeat fresh and World War I beginning in Europe, Porter went to France where he worked for an ambulance corps connected with the French military. After the war, with no musical projects in sight, Porter simply stayed in Europe, living the life of a wealthy socialite – not unlike some of the characters of Fifty Million Frenchmen.

An article in the New York Herald Tribune summed up Porter's life in the 1920s:

Broadway pleased [Porter] so little and the imagined joys of travel tempted him so much that he washed his hands of the theatrical business. But. . . even after he had decided to quit and do nothing but travel and laugh at the worries of song writing, he was fashioning tunes and juggling words into lyrics. The virus was in his system and neither the Riviera nor Munich beer gardens could get it out. Porter came back as his friends on Broadway knew he would. For ten years he stayed away, trying to tell everyone he was not working but filling a trunk with manuscripts and scores just the same.

That he abandoned Broadway completely during this time is not true. He contributed to many shows and revues, producing a few minor hit songs. By the late 20s, though, the "virus" had taken hold and Porter began his long run as Broadway's most sophisticated songwriter.

Throughout his career, Porter wrote shows populated with the rich, smart young people of the set of which he himself was a part. Some of the characters in Fifty Million Frenchmen reflect that, but there is also a skewering of the annoying American nouveau riche who, like Mr. Carroll, think that anything and everything is for sale.

Broadway shows of the era provided the flimsiest of excuses for songs, and that holds true here, even relying the tried and true formula of having a performer (May DeVere) whose basic function is to appear to entertain the other characters.

Early Porter shows – as was the case with most Broadway shows – rarely exist in a what musicologists would call a definitive edition. Fifty Million Frenchmen is no exception. As always, songs left the show during tryouts, replaced by others. Even after opening in New York, though, changes were made in the show's score. Producers and writers were pragmatic, quickly eliminating material that slowed down the show or simply was not going over.

The performing edition created by Evans Haile and Tommy Krasker, which American Classics used for their performances, restored many of the songs dropped in 1929/30. The opening number, "A Toast to Volstead" (tweaking Prohibition) was dropped five weeks into the New York run (and was not used by American Classics); "The American Express" became the first choral number in its place. "The Tale of the Oyster" was a reworking of a party song called "The Scampi," which Porter had used to entertain his socialite friends in Paris and Venice. It had originally been intended for an earlier show, Wake Up and Dream but did not see the stage in that show. Helen Broderick sang it in Fifty Million Frenchmen, but it was withdrawn during the New York run. The reasons for its departure are unclear, but apparently it made an influential critic queasy (perhaps working too well!), and this may have influenced the producers. Also originally written for Wake Up and Dream is "Where Would You Get Your Coat?"

"The Boy Friend Back Home" was added in New York, then dropped for "Let's Step Out;" both songs are in the edition used for these performances. Songs dropped in Boston were "I Worship You," "Please Don't Make Me Be Good," and "The Queen of Terre Haute," all of which also have been restored for this edition. Not in this version is a song now considered in poor taste, "The Happy Heaven of Harlem." Porter very much wanted a Harlem song in the show and, in fact, wrote two other versions before settling on this one. Also unused is "Why Don't We Try Staying Home." It is a fine example of the fluidity of scores from this era that their absence make no effect.

Another number of interest in Fifty Million Frenchmen is "Do You Want to See Paris?" It contains a number of quotes from other popular songs of the time, including Vincent Youmans's "Hallelujah" and George & Ira Gershwin's "'S Wonderful."

– Benjamin Sears