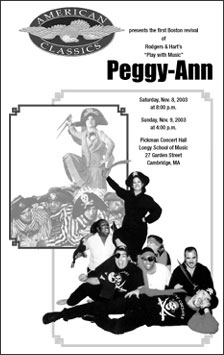

American Classics

Peggy-Ann was a critically acclaimed concert musical production presented by American Classics in 2003.

Please click here to listen to selections from the show.

"Nothing tickled me more than American Classics' concert revival of Rodgers & Hart's 1926 Freudian 'play with music,' Peggy-Ann." - Lloyd Schwartz, Boston Phoenix

When Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart first began their partnership they quickly added a third member, book writer Herbert Fields, who was the son of vaudevillian and producer Lew Fields and brother of lyricist Dorothy. They wrote a number of shows together, having their first great successes with Dearest Enemy in 1925 and The Girl Friend in 1926.

Rodgers & Hart, from the beginning, were interested in developing the musical; they wanted to find new ways to tell the stories, and particularly to find ways to integrate songs and music more directly into the stories. In 1926, with Fields, they felt ready to experiment with the traditional musical comedy form, creating what they would call a "play with music" (the first time they used that term). The result was Peggy-Ann. Their new thinking was evident immediately as the curtain went up: after the overture there was no opening number. Ethan Mordden, in his book Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s, wrote ". . . plenty of musicals before this one had begun without a chorus. What was unknown was the musical's starting without music of any kind."

The genesis of the show, in part, came from a song Rodgers & Hart had written in 1920. Rodgers, in his autobiography Musical Stages, told of that song, "called "You Can't Fool Your Dreams" for Poor Little Ritz Girl, which may well have been the first Broadway show tune to have indicated that its lyricist had at least a passing knowledge of the teachings of Dr. Sigmund Freud. By 1926 Freud's theories, though much discussed, had not yet found expression in the theatre, and the time seemed ripe for a musical comedy to make the breakthrough by dealing with subconscious fears and fantasies. That's exactly what we did in Peggy-Ann."

Mordden says of the book, simply "there was no plot." He overstates the case, but not by much. Peggy-Ann was based on an earlier musical, the 1910 Tillie's Nightmare (which gives Peggy-Ann the curious distinction of being a musical based on an extant musical), in which the Cinderella-like heroine dreams of a life far removed from the drudgery of her own existence (see photo). Other than the usual boy meets girl format, Peggy-Ann is a series of the heroine's fantasies, featuring policemen with pink moustaches (see photo), demented traffic lights, disorganized department stores, Gilbert & Sullivan pirates (see photo), and a talking fish (see photo). The story begins and ends in a drab upstate New York boardinghouse (see photo), and ultimately Peggy-Ann does not realize her fantasies except to defy her mother and marry her boyfriend, an uninspiring A&P clerk.

That Rodgers, Hart, and Fields called Peggy-Ann "a play with music" is apt. The book of Peggy-Ann, particularly in the "reality" scenes, reads like the script of a legitimate play. While the story does have stock characters, such as a trio of touring vaudevillians, they do not feel as if they are there simply to provide songs. The first songs seem unprepared when they appear, not having been set up by dialogue which can only culminate in song. The fantasy scenes use music to heighten the fantasy, rather than being mere excuses for production numbers. Peggy-Ann does not feel like a musical, but rather like a straight play with songs interspersed.

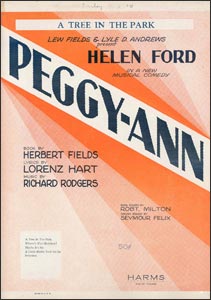

The Rodgers score is the gem of the show. By turns sophisticated, witty, and adventurous, it shows the 24-year-old composer already in full command. The most well-known melodies include "A Little Birdie Told Me So," "Where's That Rainbow" (see photo), and "A Tree in the Park." The finale to the first act (see photo) is a masterful conglomeration of reprises of songs from the show bridged by sections of music quoting Beethoven and parodying the operrettas of W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan.

Hart's lyrics may not have the brilliance of some of his other work, but they never fail ideally to catch the character or the situation. Fields's book does have some of the bad jokes and stock characters expected in a '20s musical, but it takes the Cinderella theme and neatly creates a play which has interest and does not cloy.

The original cast featured Rodgers, Hart, and Fields' favorite, Helen Ford, who had starred in Dearest Enemy in 1925. Also in the cast were Edith Meiser, Lester Cole, Betty Starbuck, Fuller Mellish, Jr., and Lulu McConnell, who most critics felt stole the show. Critic George Goldsmith called her "uproarious and irresistibly funny" and Stephen Rathbun of the New York Sun said, "it does not seem possible that any woman, or any man, for that matter, could be as funny as Miss McConnell endeavors to be."

Overall, the show's reception was somewhat mixed, with the aforementioned Goldsmith clearly hating it (except for Miss McConnell), though admitting in his review that he is a minority of one. Rathbun called it "original, fantastic, fast-moving." Alan Dale, in the New York American, said "thoroughly delightful." Some reviewers clearly understood what Rodgers, Hart, and Fields were attempting, with the reviewer for the New York Times noting, "From the beginning they have brought freshness and ideas to the musical comedy field, and in the new piece at the Vanderbilt they travel a little further along their road." Perhaps the cleverest summation came from "H.H." in the London Observer, who gave the following recipe for "this new musical play from America": "Think of Barrie, then double it. Take a Kiss for Cinderella, a Pirate or two from Peter Pan, a glance at Alice in Wonderland, and mix in some essence of Salteena. Insert slices of Revue sprinkled with Vaudeville. See that your songs are sweet and rub them in discretely. Add fresh dances to taste, and serve gaily with a generous helping of Apple Sauce a la Beggar on Horseback."

– Benjamin Sears

"American Classics did it again. Their revivals of historical musicals are the stuff of legend and Peggy-Ann races to the top of the list." - Beverly Creasey, Theatre Mirror