American Classics

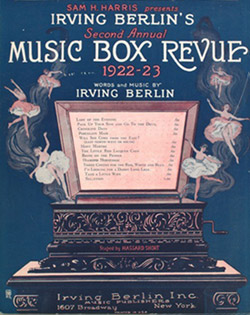

On April 8 and 10, 2005, American Classics presented a newly restored compilation of Irving Berlin's Music Box Revues 1921-24 as part of their 2004-2005 season. The American Classics production included both songs and skits from the original shows. Both shows were given at the Longy School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Please click here to listen to selections from the show.

Following is a short history of the Music Box Revues with additional comments on the songs that were featured in the two performances.

The tradition of actors, directors, and writers being their own producers is as old as the theatre itself. Rarely, however, did they go so far as to build their own theatre to house their own work. In the case of composers, with the exception of Richard Wagner (who conveniently used the money of others), a composer building his own theatre was unheard of. So, when Irving Berlin decided to team with Sam Harris not only to produce his own shows, but to build the theatre to house them, he was taking an unprecedented step and a huge financial risk.

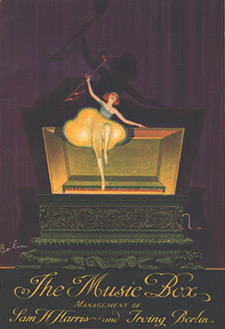

He took the risk and the theatre was built. It was the lovely Music Box in New York's theatre district, on West 45th Street, between Broadway and 8th Avenue.

Berlin's intent was to write a yearly revue called simply The Music Box Revue. This would put him in direct competition with his former employer Florenz Ziegfeld (producer of the Follies), along with many other popular revues, including George White's Scandals (and an up-and-coming songwriter George Gershwin) and later the Earl Carroll's Vanities. Berlin's reputation as songwriter, and now producer, was on the line.

The venture was a success, with the first Revue opening in 1921. Both the theatre and the show received rave reviews. Some of the leading performers of the period appeared in various editions, including Charlotte Greenwood, John Steel, Grace Moore, Robert Benchley, Fanny Brice, Bobby Clark & Paul McCullough, and the Brox Sisters. Leading writers provided skits, from the prolific Paul Gerard Smith and Frances Nordstrom (both forgotten today) to Bert Kalmar & Harry Ruby (who wrote sketches along with their songwriting) to Robert Benchley and George S. Kaufman. The latter two contributed classic scripts with Benchley's The Treasurer's Report (1923, but actually an interpolation from another show) and Kaufman's still popular If Men Played Cards as Women Do (1923).

The early '20s were also a period of new maturity for Berlin as a songwriter, now often setting the standards for popular song rather than adapting to the prevalent style. In this period, and as his own producer, he felt freer to experiment with musical form and use of language. By the time the Music Box Revue series ended in 1924 he had left behind the Ragtime craze and the ethnic songs that were such a part of his - and others' - output throughout the 1910s.

Berlin's songs (and Berlin himself) were the stars of the show, so it was no surprise that the opening chorus of the first Revue incorporates a scene about music, with eight chorus girls presenting themselves as the "Eight Little Notes."

By nearly forty years, "Climbing Up the Scale" (1923) predated Rodgers & Hammerstein's more familiar paean to the C major scale, complete with counterpoint. Both songs share a charming lack of profundity.

Charlotte Greenwood, famous for her long legs and high kicks, introduced "I'm Looking for a Daddy Long Legs" (1922), lamenting her inability to find a man "who can reach me when I'm ready to be kissed."

"Behind the Fan" (1921) drew on the fascination with exotic Spain. It was followed the next season by "Mont Martre" (1922), which used Paris for the same effect (and which song was cut before opening night). Berlin, however, goes well beyond simple effects in both songs. "Behind the Fan" tells of the danger lurking in a mysterious woman, while "Mont Martre" sings of the broken dreams found in Paris. Berlin used a tango rhythm for both songs, yet in entirely different fashions.

"Dining Out" (1921) was a lengthy scene incorporating a song that would be published separately, "In a Cozy Kitchenette Apartment." The full scene featured a couple arriving at a restaurant, singing the song, followed by a sequence in which the food, tips, and even a cigar, came to life and sang and danced, a precursor of the "Be Our Guest" sequence in the film Beauty and the Beast many years later.

"What'll I Do?" (1923) was added late in the run of the Third Revue; so late in fact that it entered the series in 1924.

The de facto theme song of the Music Box Theatre was "Say It With Music" (1921). While the song is still famous today, it is little known that it originally was a duet. For the American Classics' production in April 2005, that version was restored.

The Act I Finale of the first Revue is an extended version of "Everybody Step" (1921). It was a hit in that show, sung by the popular trio The Brox Sisters (predecessors of the Andrews Sisters), along with the full cast. It is yet another of those Berlin songs that use dancing as a metaphor for love (and more).

"Pack Up Your Sins and Go to the Devil" (1922) is Berlin in one of his finest and wittiest counterpoint songs. In all of his other counterpoint songs there is a feeling of one tune being fast and the other slow, even though they are both in the same tempo. "Pack Up Your Sins" has the feeling of two fast tunes - the second would be a patter chorus in any other song. Yet, as always with Berlin, they meld together perfectly.

"All Alone" was added to the tour of the 1923 show, then used in the 1924 edition at the Music Box. By then the series and Berlin the songwriter were both losing inspiration, so it was felt that this established hit would help the score. In the original staging the singers were at opposite ends of the stage, waiting by their telephones. Oscar Hammerstein II felt that Berlin had written a perfect lyric with "all alone by the telephone," because it told the entire story in just five words.

A quintessential chorus girl song, "I'm a Dumbell" (1921), was exactly what would be expected in a short comedy number.

Berlin was a great fan of the opera, regularly attending New York's Metropolitan. His knowledge of opera was wide and in his early songwriting years he delighted in using opera both as a model and for parody. His second show, Stop! Look! Listen! has the Ragtime Melodrama, which is as close as he came to writing a one-act opera; his first show, Watch Your Step, features an opera parody much in the style of the burlesque of Yes, "We Have No Bananas" (1923) which was new restored by Bradford Conner for the American Classics' production in April 2005. Bananas would be the last of Berlin's opera parodies and has the distinction of drawing on both popular song and opera. Featured melodies were from Verdi's Aida, Rigoletto, and Il Trovatore, Puccini's La Bohme, Offenbach's Les Contes d'Hoffman, Wagner's Lohengrin, Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, the popular song, "La Paloma," and even Handel's oratorio Messiah.

"Take a Little Wife" (1922) was an off-beat love song which owes a debt to Gilbert & Sullivan, even quoting a famous lyric from HMS Pinafore.

"An Interview" (1921) was Berlin's star turn in the first Revue, and his last major stage appearance other than the World War II benefit show This Is the Army. For the "Eleven O'Clock" spot, the Eight Little Notes reappeared as the Eight Reporters in order to interview Berlin, asking him how he "says it with music". He then told of his life as a songwriter in a medley of snippets from his hits, including "The Ragtime Violin," "I Want to Be in Dixie," "Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning," "Alexander's Ragtime Band," "You'd Be Surprised," and "Nobody Knows and Nobody Seems to Care." The interview concludes with Berlin's latest song hit, "All By Myself." Also quoted is "Say It With Music" (sung by the Eight Little Notes) and the introduction is drawn from "Tell Me, Little Gypsy."

By 1924 the strain of turning out a yearly revue score (as opposed to that for a book musical) was having its affect on Berlin and, realizing that he could turn a profit by renting the space, Berlin closed the series for good (though with occasional thoughts of a one-season revival) and turned his attention to other projects. However, the four Music Box Revues were the transition from Berlin as Tin Pan Alley songplugger to the confident songwriter who would write the scores for Top Hat, Follow the Fleet, and Carefree for Astaire and Rodgers in Hollywood, and Annie Get Your Gun and Call Me Madam for Ethel Merman on Broadway, along with many other successful songs, films, and stage shows.

– Benjamin Sears

*Photos courtesy of the Rodgers and Hammerstein Organization